AI and Creativity - Alex Roddie and James Carson

Is AI an existential threat to creativity? Or an increasingly necessary part of how we work in the modern age? I asked two creatives to exchange views - here's how it went down.

At this point you can divide the response to the increasing ubiquity of generative AI into four broad categories.

In the early adopter camp are those who have decided it’s the future, and are jumping in zealously with both feet.

My contact with this community tends to comes via the 5 to 10 sales emails I’m currently receiving per day, sternly warning that if I don’t completely automate my agency All Conditions Media with immediate effect, the company will self-destruct within a matter of months.

Or it’s on LinkedIn, where they post things like ‘Interested in learning how I used ChatGPT to automate my 18-step morning routine habit stack? Comment ‘YIBBLE’ to find out more and I’ll send you the secret sauce’.

Then there are the dabblers: a larger constituency who are fairly au fait with tech, and realise with a sinking heart that they’d probably better get with the programme at some point soon.

They’ve pissed about with Midjourney and Chat GPT’s Studio Ghibli thing; and begrudgingly accept that using Granola for note-taking, Claude for copy-editing, and Apple Intelligence for instant transcriptions has made their life better. (I put myself in this camp, for what it’s worth):

This constituency are increasingly the target market for the increasing number of early adopting agencies and entrepreneurs pitching generative AI in a very particular way.

In this beguiling telling, AI is a short cut (basically: we write the prompts; you use them) to the sunlit uplands of more time for more (ahem) ‘deep work’.

See David Hieatt’s ‘The Fifth Day’ course (‘for the founder who wants a life, not just a business’) for a sophisticated version of this pitch aimed at solo entrepreneurs, for example.

Then there’s the vast majority, who are too busy living actual lives, have vaguely heard of AI, have no idea what it really is, certainly have no idea how much it has infiltrated their lives already, and have no intention of exploring the topic more any time soon. For right or wrong, I would put almost all of my friends, family, colleagues and acquaintances in this group.

Finally, there are the die-hard none-adopters, who see it is a scourge on … well pretty everything. Resources. Creativity. Employment prospects. The fabric of society. The quality of discourse. Whatta ya got?

And it’s a proud member of the latter constituency who actually inspired this latest Open Letter exchange: my pal Alex Roddie, editor of Sidetracked and Like the Wind Magazine, self-professed AI Luddite (a word he uses deliberately, knowing full well the provenance of this particular phrase, and the emotional freight it carries), and defiant generative AI party-pooper.

In the last months, Alex has been posting a series of passionate polemics (like the one above) that argue strongly against the way we are creeping into an AI future without fully interrogating the ethical, creative and societal implications.

It is fairly common (at least on my timelines) to see people taking this position in some vague ‘but … what about the energy usage?’ sense. But I haven’t seen anybody make the point as forcefully and convincingly as Alex. OK, maybe apart from Ken (below).

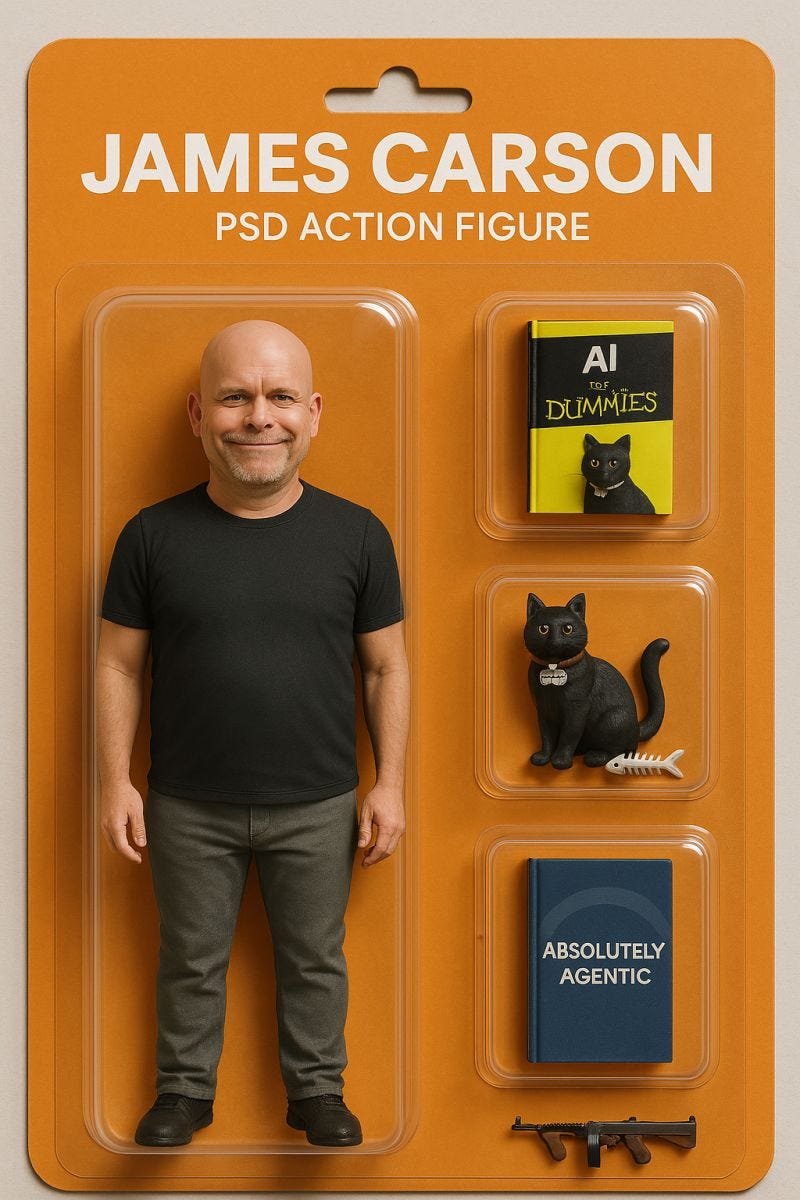

So I asked him (Alex, not Ken) if he’d be interested in debating his views with another friend James Carson, who runs an agency called Absolutely Agentic, through which he offers ‘AI consulting and automation for content companies’.

I did some work with James about a decade ago. Since then, I’ve followed him on LinkedIn, where, like Alex, he gently challenges the standard cliches and shibboleths of the AI debate, albeit from the other side of the argument. Happily, they both agreed.

As with previous Open Letter exchanges, this conversation is about understanding different perspectives, not skewering one particular constituency or viewpoint.

(You can catch up with a couple of previous back-and-forths using the links below:)

Here’s how this one unfolded. Have a read and let me know what you think.

1. James Carson:

Dear Alex,

In the last three years, generative AI has pretty much impacted every type of creative medium: image, text, video and game development - in roughly that order.

What was initially an unreliable assistant can now create outputs of very high standard in image and text, and it’s only a matter of time before the same occurs with more complex generations like video.

I think we can tie ourselves in knots about the ethical quandaries relating to AI and copyright. But the genie is out of the bottle, and there’s little we can do about it.

We can complain and refuse to use it, but I can’t see how that will help. Regulation has proven far too slow and muddled on earlier technology like social media for complaining to have much impact.

I’d also argue that copyright theft on social media has long been rife and the law never really caught up. The double edge to the sword is there will inevitably be a ton of people who use it effectively, regardless. They’ll likely be able to have a much higher rate of productivity, and consistently high quality, if they already have pre—existing creative skills. This puts the refuseniks at a severe disadvantage in an economy dominated by AI.

And it will be dominated by it - AI is likely to be the most transformational technology in history. Getting with the programme is no longer optional.

Yours,

James

2. Alex Roddie:

Hi James,

I disagree that AI can produce work at a genuinely high standard – unless you set the bar low. It's always going to be a fake semblance of human communication or, at best, a technically accomplished rehash devoid of meaning or nuance.

To dismiss valid ethical concerns around AI is to play into the hands of power-hungry tech companies who think they can break the law without consequences. It also shows contempt for creatives. I agree that governments have failed to regulate big tech, but that isn't an argument for giving up – especially now the stakes are higher.

The problems creatives face have nothing to do with poor productivity or barriers to quality. Creatives struggle with poor-paying, precarious work because big tech has blown up profitable business models. Making creative work faster or more efficient doesn't make it better and in the long term it will only further degrade pay in creative sectors.

Creativity comes from doing the thinking as you create the work. Avoid this and creativity evaporates. What about those entering the workplace? Where are they going to develop their own unique taste and perspective? You're describing a race to the bottom.

Creatives can compete by developing valuable skills and their own human perspective, then focusing on sectors that value these things. Others can automate themselves out of the workplace if they wish.

Finally, there is no evidence that AI will be the most transformative technology in history. In fact, there's little evidence it's even profitable.

Alex

3. James Carson:

Dear Alex,

Part of the problem of 'all or nothing' thinking about creativity and AI is that the presentation of quandaries and ambiguities can be framed as 'dismissals' and 'contempt for creatives'. It’s possible to be ‘creative’ and see the benefits of AI. I put myself in both camps. But this is as much one of the perils of debating emotive topics as anything else.

A similar generalisation problem plays out when it comes to definitive statements such as ‘AI can’t produce work to a high standard’.

If the image above had been created by a human five years ago, it’s difficult to imagine people would describe it as low quality. If an AI video like this can tell an educational story of an extinct animal that teaches young children about environmental issues, does that not have value?

Regarding productivity - before AI video editors were painstakingly transcribing and inputting subtitles onto videos. Now an hour-long task is compressed into seconds. In this case, not taking advantage of the technology means losing hours to your competition: ie, someone using AI.

30m+ creative people are subscribed to Adobe Creative Cloud - which increasingly has generative AI features. This huge user base is counter to the general charge that AI is not profitable. Almost all software will have AI features added to it over the next five years.

It is accurate that OpenAI is not profitable, but it's just one company. Midjourney, which is an archetypal AI -based creative tool, is profitable - with $200m in annual revenue via under 50 employees. It is also not ‘Big Tech’. It hasn't taken investment.

While it's difficult to show 'evidence' for things that haven't happened yet, there is a huge amount of academic literature on the potential of AI, both good and bad. I admit I am concerned by some of the potential downsides. But I believe the upsides will be more significant and transformational. Does a survey of 2,778 academics count as ‘no evidence’?

James

4. Alex Roddie

Hi James,

Although I welcome your call for nuance, I wonder how this fits with arguments such ‘getting with the programme is no longer optional’, and framing legitimate concerns as ‘complaining’.

I have no objection to tech that’s developed in consultation with the people it will disrupt – if it primarily exists to empower them.

As I see it, most AI tools exist primarily to empower companies and managers looking to save costs – not creatives looking to produce better work, improve their earning potential, or find satisfaction by exercising different skills. I’ve seen no evidence that AI can do better work; only that it can do some things more quickly and cheaply, while requiring less skill.

Since the Industrial Revolution, such technologies always primarily benefit capitalists and managers. They’ve been used to eliminate roles, de-skill, and drive down wages. And for 200 years they have concentrated wealth at the top of the economic food chain. Where’s the empowerment in being forced to compete with others who use AI to do faster and cheaper work? We only have to look to the history books.

I’ve used Adobe's AI sky masking and denoise myself. They do save time, but the details can be iffy – you're better off putting more effort into taking a better initial picture. I also know professionals who resent the intrusive AI updates. Although Creative Cloud itself is profitable, I think it’s disingenuous to claim that’s due to the AI – there’s no evidence to support this.

A freelancer can choose not to outsource their decision-making to AI, instead using it to automate repetitive tasks – great. But what about a worker at an agency or publisher, told their job is less valuable because software can now do 70% of it?

I agree it’s a nuanced situation, but messages from prominent AI evangelists declaring the end of all creative jobs are far from nuanced. The fact that creatives were not even considered before our work was stolen to train these tools speaks volumes. Given these aggressive attacks, I believe resistance is a moral imperative.

Progress is never equal. But technology can and should be developed equitably.

Alex

5. James Carson

Hi Alex

I don't believe AI will be optional, but I do believe in nuance. For example, that you've stated your opposition to AI, while also admitting you use it, is a nuanced case.

To take your points in turn:

We'd all like to capture better content in the first place, but at times that's not possible. If you record an interview and there's someone blowing leaves outside and you can't get them to stop, that's not really anyone's fault. These absurd scenarios are irritatingly common, yet AI can help sort them out quickly.

If a technology increasingly becomes a prevalent feature of existing profitable software, then of course it contributes to profit. As I say, beyond Adobe there are plenty of AI startups that have achieved profitability (see above).

The list will go on.

The interpretation of the Industrial Revolution is interesting, but it's not one I'm familiar with, and I find it pessimistic. I say that as an editor of two history books which sold pretty well. While that event was disruptive if you were, say, a handweaver; the overall benefits in terms of societal wealth were vast.

Prior to it, most people were living shorter lives governed by the seasons, working on patches of land owned by a landlord. i.e, they were literally peasants.

Life is vastly better now than it was in 1750. AI has the potential to make similar transformations far more rapidly. Implying that the only beneficiaries of technology are capitalists is to look at history through a Robin Hood lens.

When it comes to this ides that AI means the end of all creative jobs: who are the prominent AI evangelists saying this? I don't see many 'prominent' people saying that - largely attention seekers on social media.

Finally: I don't doubt that some of it appears pervasive, but AI has also arrived with overwhelming force. Thus it has a certain inevitability.

Cheers

James

6. Alex Roddie

Dear James,

It’s been an interesting discussion and I’ve learnt a lot from it, although if anything I’m more worried now than I was at the start! Nevertheless, thanks for engaging in a respectful manner.

I totally agree that AI isn’t going away, and you’re right that some people will figure out a way to profit from it. It certainly isn’t useless! But no technology is inevitable. Development happens due to management decisions. These can either be made with the consent of workers, for their benefit, or not.

As I write this, Duolingo has just announced they plan to replace contract workers with AI.

Sam Altman, probably the most prominent AI evangelist, has said: '95% of what marketers use agencies, strategists, and creative professionals for today will easily, nearly instantly and at almost no cost be handled by the AI.’

It worries me that your knowledge of the Industrial Revolution seems to be a little one-dimensional. I agree that life, for most people, is better now than it was in 1750. But it took over well a century for life to materially improve for the artisans whose professions were eliminated. The factory system led to an era of misery for British working people. Entire ways of life were destroyed.

For multiple generations, previously skilled craftspeople were trapped in a system where they earned less money doing less engaging work, had less freedom, spent less time with their families or in contact with nature, and died younger. These are all well-documented facts.

Apart from a small number of wealthy industrialists, the Industrial Revolution made almost everyone’s lives worse for many decades until things gradually started to improve for the majority. It also caused the climate change that may eventually end civilisation as we know it, but that’s an aside!

I see history repeating itself. I see direct attacks being made against my profession and calling, and I’m not going to take them lying down.

I’m not arguing for a halt to progress. I’m arguing for craft and integrity. I’m arguing for us to be intentional with how technology is adopted, honest about who it will benefit, and to think about what we want human creative work to be in the future.

Yours,

Alex

What did you think of this exchange? Do Alex and James reflect your views on AI and creativity? How do you think we should approach the challenges ahead? Let me know using the button below:

Really appreciated this conversation. It’s rare to see this kind of care and depth in a discussion about AI. Alex I really felt the weight of what you shared around the emotional and ethical sides of it all. There’s a lot in here that made me pause and reflect.

In the creative and neurodivergent communities I’ve been part of AI hasn’t replaced creativity. It’s helped give access to it. For people like me and many others with ADHD or dyslexia the hardest part of the process isn’t always coming up with ideas. It’s staying with them. Getting them organised. Finishing. Traditional systems can be overwhelming and often aren’t built with us in mind.

Through the UK’s Access to Work scheme I’ve had support from a neurodivergent workplace coach and together we’ve built a rhythm that suits how my mind works. I often record conversations or voice notes then use AI tools to transcribe and reflect on what’s there. That part helps me make sense of patterns or ideas I might miss in the moment. It’s not about getting AI to do the creative bit. It’s about helping me stay with the work long enough to shape it.

This has been a big shift in my practice. With photography, film, and storytelling it helps me stay connected to what matters rather than rushing to keep up or forcing a process that does not fit.

I don’t say any of this to dismiss the very real concerns around AI. The questions about ownership, power, and sustainability really do matter and I hold that too. This is just a window into a part of the creative world that often gets left out of these conversations. It is a space where AI, when used carefully, can actually help people stay in the work instead of being pushed to the edge of it.

For a lot of us it’s not a shortcut. It is a way in. It is a way to stay present with creativity in a world that often feels like it was built for someone else’s pace.

Viva La Resistance!!

Although I do see AI as a tool, as Alex and Tim have said the lack of governance/ control does put peoples livelihoods, not just creatives, at threat. Is it just me that thinks the fact 128 people made $390M in a year from start up using AI is crazy / concerning? (I added them up in head from the graphic in the stack, apologies if they’re not accurate) I know some publications, agencies and brands have made AI policies which is great and sets out their stall on what is acceptable usage. The quick changing landscape of AI’s ‘powers’ will require policies to change as quickly.